Old age is a creeping horror for a lot of people, and it’s understandable. It’s indicative of a body reaching its limits. Wear and tear, rust and a bit of decay. Perhaps one of the most underrepresented aspects of this stage of life is our waning ability to stand up for ourselves. Little by little, the prospect of putting fists up or outrunning a threat becomes ever more difficult. Eventually, all we can do is scream for help or push the nurse’s button near our hospice beds quick enough for assistance. Director James Ashcroft’s The Rule of Jenny Pen is an exploration of this, and it manages to paint a terrifying portrait of it thanks to the masterful performances of its three leads: John Lithgow, Geoffrey Rush, and George Henare.

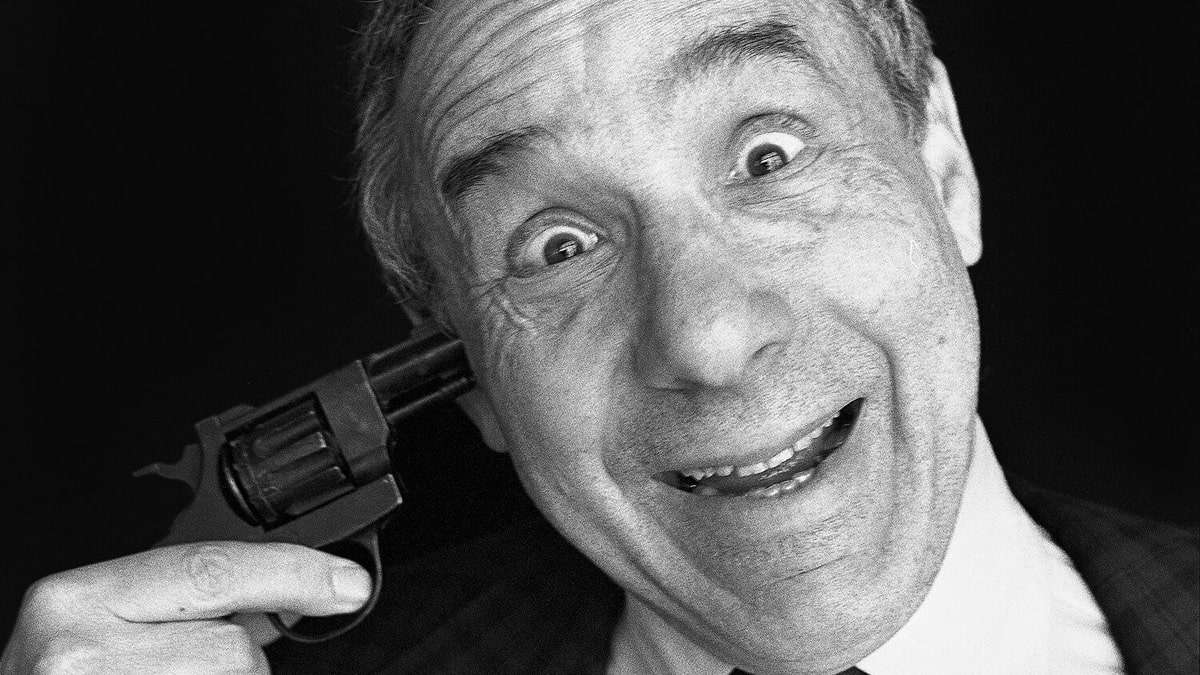

Jenny Pen takes place in an assisted living facility. Their most recent admittee is judge Stefan Mortensen (Rush), a man who suffered a stroke while on the job and is very keen to leave the facility as soon as he’s able. While there he reluctantly befriends Tony (Henare), a retired athlete with whom he shares a room with. It doesn’t take long for Stefan to realize they’ll share in something else as well, namely the wrath of another elderly resident called Dave Crealy (Lithgow). This towering man, more able-bodied than most of the other patients there, carries around a creepy baby hand puppet that he uses to terrorize the other residents at night. He takes an interest in the judge, and so very ugly things start to happen.

The movie hinges on the believability of the cast’s elderly struggles, both their helplessness and their ingenuity in the face of it. Lithgow, Rush, and Henare capture this with a palpable sense of tension and threat.

Rush’s Stefan is largely wheelchair-bound, but he remains resolute and of strong character throughout. Henare’s Tony is living the consequences of putting his body on the line for his sports career, and he plays it with a sense of determination coupled with a bit of sadness that makes him perhaps the breakout character in the story. Lithgow’s Crealy represents power, a variant of old age that hasn’t completely incapacitated him. His presence looms over the facility like that of a vampire’s, taking to the night for his torturous games. Lithgow lands his New Zealand accent on every single line here, and he manipulates it well to allow it to come off as a uniquely evil scowl.

Each performance centers on a different variation of old age and the specifics that accompany them. They make sure to highlight strengths and weaknesses to make it authentic to the story so as not to turn anything into caricature. For instance, Crealy, while more physically capable, has asthma and he has to keep from overexerting himself. The performance always keeps that present, so viewers remain aware of the fact that time is inescapable and that it will catch up with everyone one way or another.

Henare approaches this by framing any kind of physical activity his character does as an arduous chore that looks painful every step of the way. His walk is slow and heavy, he takes his time eating, and he gets tired easy. That said, he’s of sound mind. He might not be able to fight off Crealy on his own, but there still some things he might be able to do with what he’s got left. In a sense, Henare’s Tony becomes the heart of the film, standing right in between Stefan and Cleary in terms of how age has dictated his reality and his place in the facility. Henare conjures a lot of sympathy for his character, to the point that the movie could’ve just let him be the lead rather than Rush in the struggle against Cleary.

Director Ashcroft goes lengths to present the story as an absurdly realistic look at old age, and one that isn’t afraid to play around with tone at that. The first half of the movie is full of dark humor that pokes fun at our attitudes towards becoming old and how the people who work in these assisted living facilities are like lazy phantoms that have decided that the elderly are essentially old babies that need to be treated as such, or even disregarded when it suits them.

Once the movie reaches the halfway point, though, the tone just takes a sharp turn into darkness. The pacing takes a hit and the cruelty on display becomes a bit repetitive. The movie just dives into suffering in a manner that betrays the humor it establishes so well in the beginning. It never dulls the performances or betray its portrayal of the relentlessness of time, but it certainly makes it less interesting.

Had it stuck to the first half’s stylings, it would’ve hit harder come the final act. When the closing confrontation happens, you’re just happy the pain is over and done with. And this is despite Ashcroft’s decision to get more creative with Cleary’s baby hand puppet later on in the movie. Some great horror sequences come out of it, but they also could’ve been set up a bit earlier.

Despite this tonal discrepancy, The Rule of Jenny Pen is a great example of how to create believable elderly characters. Each achievement rings true and feels legitimately triumphant because of the stuff they have to overcome because of their advanced age. This is quite a thing to pull off, and it should generate excitement for whatever James Ashcroft comes up with next.

Source link