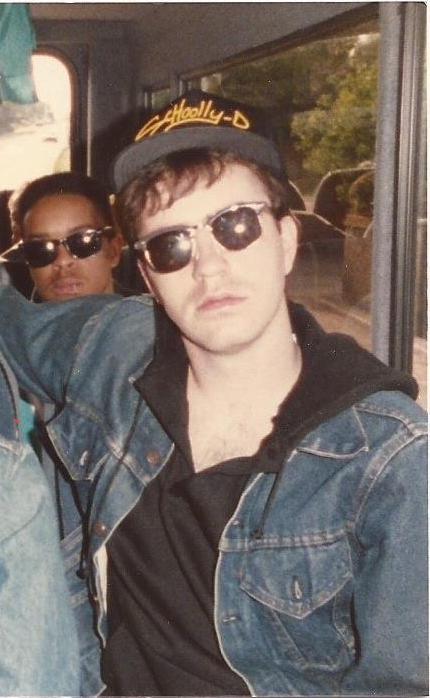

I released the first known gangsta rap album, Schoolly D. Some Spin journalist called the genre “gangsta rap” because he was interviewing these gang members in Baltimore and all they were listening to were my songs, like “P.S.K. What Does It Mean?,” so the journalist said, “This must be gangsta rap.” And that is how that all started.

Schoolly D tells Philadelphia Magazine how SPIN gave the genre its name

CHRIS SCHWARTZ: The importance of Schoolly D’s “P.S.K/Gucci Time” to the rap world cannot be overstated. The landmark 12” vinyl, widely acclaimed as the first ever gangster rap record, is among the most influential records in hip-hop history, and served as a career-launching inspiration for Ice-T, Eazy E and NWA, among many others.

More from Spin:

- The Senator Is Pissed Off

- Rappers Choose the Best Rap Albums of All Time

- Pubilc Enemy, Ice-T Lead D.C. ‘Celebration Of Hip-Hop’ Concert

Not only did “P.S.K.” inspire an all-new rap genre, it was also the first completely independent project in hip-hop. And we’re not talking about an independent label—”P.S.K.” was the work of one man. From start-to-finish–writing and producing, to recording, mixing, artwork and sales—the single was all Schoolly.

My journey with the game’s first gangster rapper began in the early-80s at a daycare center on 52nd & Parkside Ave. in Philadelphia, where I worked for an independent record label on the second-floor. The label was called Nicetown Records and was run by an ex-prison guard by the name of Ted Wing.

Ted and Nicetown had put out a few ‘nice’ records, namely Bunny Sigler, and Bill Cosby’s Hardheaded Boys, recorded live at Graterford State Prison. Ted was in charge of prisoner activities at Graterford, which scored him the Cosby standup record.

I was 21 and eager to start my own label, and the day I told Ted I was leaving he went into a pretty hefty speech, during which I zoned out and my eyes drifted towards a new stack of records by his desk, labeled Schoolly D “Gangster Boogie”. Ted caught me staring and mentioned they were from a local guy in search of distribution, (whom he sent packing). I knew of Schoolly from WHAT radio, and at the end of my last day, I grabbed Schoolly’s number off Ted’s desk.

After a good bit of calling, chasing and convincing, Schoolly and I assembled a plan to work together, and the afternoon that deal was struck, he gave me a test pressing of his new double A-side “PSK b/w Gucci Time”. Returning to my home studio at 48th & Hazel Ave in West Philly, I put “P.S.K.” vinyl on and could barely comprehend what I was hearing.

Almost every rap song on the radio at that time was a gimmicky track about girls and parties. Horns and keyboards, just hokey stuff. But this? The “P.S.K.” beat was like nothing I had heard in my life, so dark and cavernous and dusted. Snares like air compressor bursts in an aircraft hanger. Cymbals like eerie warning bells, a kick that resonated like a slow-motion earthquake.

The subject matter was groundbreaking too. While most rappers were still coming with that “yes-yes y’all…to the beat y’all” lyric style, Schoolly did the unheard of, presenting dark gangster narratives, issuing warning shots on wax, which after growing up in Parkside section of West Philly in the 70s, he didn’t really have to make up.

At age 12, Schoolly was running with his older brothers, members of a collective of teens that controlled the weed trade in a 5-by-6 block area near Fairmount Park in Philly. Within this square, any other enterprising dealers needed strict permission from the home crew to do business, and so no one forgot, painted almost everywhere in conspicuous, day-glo spray paint were the capital letters P.S.K.: the Park Side Killers. Any sales without P.S.K. sanction earned you a brutal beatdown and confiscation of your shit.

The Park Side Killers’ firm rule over their territory didn’t stop with drugs, but extended into other assorted realms of crime such as fencing stolen goods, and boosting extreme amounts of clothing from shopping malls by creating elaborate diversions while neighborhood girls walked out with thousands of dollars worth of merchandise.

The P.S.K. crew answered to a larger criminal organization of immaculate older gentlemen, who as a kid, Schoolly watched prowl the block in Lincoln Continentals, Cadillac Coup de Villes and Eldorados. Silk shirts and cashmere turtlenecks, custom suede bombers, fitted ostrich or python boots, talking in clever metaphors with a distant, lazy cadence—Schoolly cites these hustlers as the true inspiration for “P.S.K.”

The record’s cover on the other hand, is the complete opposite of their aesthetic. While most rap releases of the time featured sleek photos of artists dressed in their flyest, the “P.S.K.” artwork was just a bit, let’s say, unpolished. The pimped-out gangsters from the lyrics are nowhere in sight, only self-portrait cartoon sketches of Schoolly with exaggerated features, locked in a diatribe with a cigar-chomping, blockhead authority figure resembling a high-school principal.

The single’s A-side label features a comic book silhouette of tall, black buildings, with a funky 1960’s Robert Crumb-style space capsule on the B-side. Both the cover and these labels were simply drawn graffiti-style over a school bus yellow background. At a time when all artists sought to project corporate legitimacy and earn lucrative distribution deals, Schoolly’s approach was revolutionary, and gave “P.S.K.” an appeal that luxury gear and big-spend marketing couldn’t buy.

As the record blew up, though, we did need a better distribution solution than a car trunk, and due to what we’ll call ‘tangled-up business relations’ with the two biggest vinyl plants in New Jersey, we were left scrambling for a way to fulfill our product needs. One day I came across a children’s record that had somehow made its way into a local studio I was visiting, and out of curiosity I took a look at the production plant info–“Manufactured By Peter Pan Records, Newark, NJ.”

I figured it was worth a try, but upon my first call, a secretary immediately told me they didn’t press records for outside clients. Extreme needs however call for extreme measures, so I decided to drive to Newark in person. To ease my introduction, I bought $250 worth of Chinese food, and upon arrival, told the receptionist it was a delivery for the sales staff. She directed me to a conference room, where I spread out this crazy amount of food, and dozens of duck sauce packets, then sat down and waited.

When Peter Pan’s G.M. came in and asked just what was going on here, I mentioned I was here to discuss a project. He shrugged, left, and came back with a crowd of older men in suits who descended upon the food immediately. Few words were spoken as they filled, ate, then refilled plates (with some of them going for a third round). I tried my best to break the ice and explain my production needs, but I was essentially ignored, and soon began to think I should’ve bought some lower-quality takeout.

Just when I thought it all seemed for nothing, the head of the company finished up and asked “So, Mr. Schwartz, how can we help you today?” I pulled a thick stack of purchase orders out and handed them around the table, and from their eyes I could tell they knew I wasn’t playing—I wanted 28,000 records. Within 10 minutes, we struck a deal and I headed back to Philly having convinced Peter Pan, the biggest childrens’ record label in the country, to press hip-hop’s first gangster rap record.

Before I knew it Schoolly was touring Europe—then Australia and New Zealand—with me along for the ride, hanging on for dear life. Every stop we made was a place that had never seen or heard of rap music. Some people loved it, and those shows felt life-changing. Sitting side-stage, every night I got to see fans discover a whole new world of music. Then there were those odd, rural parts of Scotland where they pelted us with bottles and cans, then chased us out of town. Memorable all the same.

Five years ago, Chuck D told me the “P.S.K.” single was what had inspired him to first pick up the mic, and that when Public Enemy hit Philly for their first show, he had their van drive them to 52nd and Parkside for a tour of Schoolly’s neighborhood. It was at that moment I realized my desperate Chinese food mission to Peter Pan was, in some strange way, part of the formation of Public Enemy. Now that’s a true mind-bender.

“P.S.K.” would go on to become one of the most sampled songs in rap history, utilized by The Chemical Brothers, The Beastie Boys, Siouxsie and the Banshees, Notorious B.I.G. and Nicki Minaj, among others. I’m extremely proud to have helped Schoolly D push the art of rap into a new age, and am not surprised in the least, that decades later, “P.S.K.” is still prompting listeners to ask the eternal question–“P.S.K., What does it mean?”

Chris Schwartz is the cofounder of groundbreaking hip-hop label Ruffhouse Records (The Fugees, Ms. Lauryn Hill, Wyclef Jean, Cypress Hill, Nas, Kris Kross, DMX, Beanie Sigel, State Property). Throughout the ’90s, Ruffhouse sold 120 million records worldwide, earning numerous Grammys while accumulating 250 gold and platinum records.

Chris’ 40-year friendship and business partnership with Jesse ‘Schoolly D’ Bonds Weaver continues to this day, with the recent release of Schoolly’s “Cuz that Ni**is Crazy! Thats Why!” LP, distributed by boutique vinyl label Ruffnation Entertainment.

To see our running list of the top 100 greatest rock stars of all time, click here.

Source link