In Music and Life, Ray LaMontagne Cherishes Things That Last

If you know of an old house for sale around the Berkshires in Western Massachusetts, preferably pre-1800, we might have a buyer.

“My sweetie and I are just crazy about historical homes, early colonial architecture and old homes,” says singer-songwriter Ray LaMontagne, his “sweetie” being his wife, poet Sarah Sousa.

More from Spin:

- Mamaleek: Utter Enigma and Understandably Human

- Snapped: ISOKNOCK’s 4EVR Gallery Event (A Photo Essay)

- Garbagebarbie Rises From the Rubbish

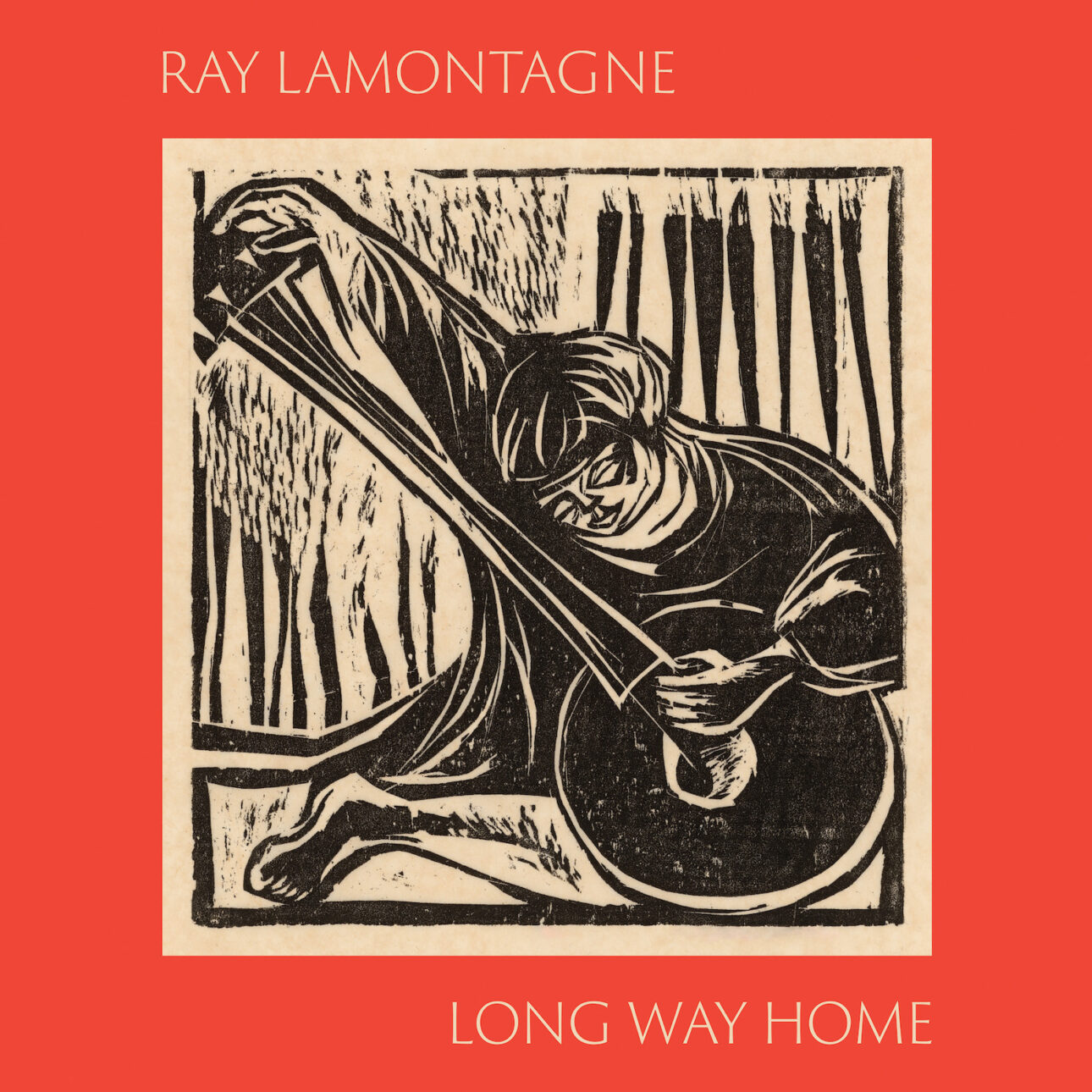

For 16 years they’d lived in an historic house on a sprawling farm, doing a lot of restoration work in that time. But last year, with their two sons grown, they “felt like it was time for some new thing,” he says. They haven’t found it yet, instead having moved between a few temporary residences while they shop, a period in which he recorded his new album, fittingly titled Long Way Home.

“We’re on the treasure hunt for a nice old house,” he says, on a video call from their home-at-the-moment. “It’s fun. It really is.”

The draw? He turns rhapsodic.

“There’s so many stories in those old houses,” he says, his voice soft and gentle, a contrast to the gruff growl which introduced him to the world via his breakthrough hit single “Trouble” and his debut album of the same name. “You can see where everyone walked, where they stood to wash their hands…the doors they touched over and over and over again. All that stuff. It’s all stories. It’s a link to something real, to the past and history and other lives that have been lived and gone.”

His eyes glint, mistily. “So, so magical,” he says.

It’s not a stretch to say that he’s tried to invest his music with the same attributes. “My biggest hope is that when I’m gone and no longer on this planet, but on some other plane doing my thing, I just hope that the records hold up,” he says. “I hope that some kid flipping through the stacks or whatever—that’s what I used to do, at the used record stores—will just stumble across one and give it a chance, take it home, and then be like, ‘Whoa, this is great. My dad was listening to this.’ Just grab it and discover it. That’s all. I just would hate to think that all of this hard work and learning to trust myself and believe in myself and just the fact that I’ve done it and built a career, that all of it just put more mediocrity into a music business full of mediocre music. Because that would be really sad. That would break my heart. I just hope it stands up.”

That crate-diving kid in the future might well stand up when he puts on the first song on Long Way Home and a couple of verses in on the first song, “Step Into Your Power,” hears LaMontagne in that gruff voice command, “Now listen!”

The message? “Power” is an anthem of self-reliance, an affirmation of inner strengths, an expression of the value he places on solid homes and a solid life, that whole thing of trusting and believing in oneself. It’s set to a buoyant, Stax-evoking track he co-produced with regular partner Seth Kauffman, with background vocals from the Secret Sisters, who appear on three of the album’s songs.

“It’s a nice reminder,” he says. “Whether it’s just me reminding myself that everything you need to be who you are and who you are meant to be is given to you. Innately, it’s in there, and you don’t have to look outside yourself, be told who you are or if you’re good enough or if you’re this or that. You know what I mean?”

It’s a thread through the whole album, songs of a settled satisfaction interspersed with odes of love and idyllic journeys held in contrast to the madness of modern life—largely sung in a gentler, airier tone closer to his speaking voice, the music mostly built around acoustic guitars, some keyboards, and drums, a pedal steel here, some strings sounds there.

“If I had the chance to turn back time, I can tell you this, my friend—I’d do it all over again,” he sings in “I Wouldn’t Change a Thing,” while in “Yearning” he celebrates holding “my baby in my arms” as they lay on the grass at night feeling “the earth beneath me just spinning around.”

As for that love, there’s “My Lady Fair”—“just one of dozens of love songs for my sweetie,” he says.

“I’m one of the fortunate few,” he says. “I mean, I’ve known Sarah since I was 8 years old. And she was my sweetie when we were 17, and she still is now. That doesn’t happen every day. It’s just a gift. I wouldn’t be the person I am without her friendship and support all through life. The whole journey has been together.”

Regarding his difficult relationship with life outside of that, he’s passionate as well. He cites values he’s held in his life and the way he’s gone about his career since his impressive debut, which came only after he’d turned 30, having worked various jobs (a stint in a shoe factory, years as a carpenter) while he and Sousa started their family, home-schooling their sons while she pursued her masters degree.

Discussing “I Wouldn’t Change a Thing,” he’s a man with purpose.

“That’s another song where after it was done I can analyze it a little bit and say that…nothing has been easy up to this point,” he says. “I’ve never had one spot where life has been easy. It’s always been a challenge in one way or another. And building a career in the music business has been nothing but a challenge. It was all done the hard way because I don’t take photographs and I haven’t done a lot of interviews and all that stuff. I just don’t really like to do it. So I don’t.”

And of course not everyone in the business gets it. “I remember a really famous artist telling me—sitting me down to tell me this—‘Ray, you need to get your face out there more. Being famous is about making other people want to be you. That’s the fame game, man. You gotta get your face out there, show them a lifestyle they want to have,’” he says, a look of bemused disgust on his face. “I remember this specifically because I just thought, ‘That is so vacuous.’”

He lets out a dark laugh. “That’s a pursuit I don’t want,” he says. “To create an image to make people envious of me in some way, to think that they have to have my life. And then that’s fame? That’s gross.”

Once again, he wants fans to relate to him the way he related to his music heroes. “I just hope to keep some veil between myself and the world, like there was when I discovered Van Morrison and Crosby, Stills & Nash, or getting into Neil Young and Joni Mitchell and then the Who and Led Zeppelin. You didn’t know anything about these guys. You couldn’t just type it in and find it. Didn’t exist. I’ve tried to walk a fine line and keep some kind of a veil between myself and the listening audience so that there’s at least some semblance of mystery. Do you really need to know everything about me?”

He laughs. “It’s such a weird world. I love that mystery. I loved listening to Van Morrison and not knowing anything about the man whatsoever and just having the music or whatever he was channeling in there.”

Whatever LaMontagne is channeling, it’s led him through some twists. His first four albums—2004’s Trouble, 2006’s Till The Sun Turns Black, and 2008’s Gossip in the Grain, all produced by Ethan Johns, and 2010’s God Willin’ and the Creek Don’t Rise, produced by LaMontagne—featured various takes on folk-soul-rock singer-songwriter forms. The song “Trouble” was featured in several TV shows and movies and in a seemingly ubiquitous insurance company commercial, while the love ballad “You Are the Best Thing” from the third album became his biggest radio hit. But then, tapping the Black Keys’ Dan Auerbach to produce 2014’s Supernova, Jim James of My Morning Jacket for 2016’s Ouroboros, and again producing himself on 2018’s Part of the Light, he experimented with both sounds and forms, heading into psychedelic and even prog territory at times.

“I was just trying to paint with different colors,” he says. “I was just hands-off—just whatever the songs wanted to be, I’m going with you. And that’s really working for me. I feel like I’m doing my best work from that point on.”

For Monovision in 2020, though, he came back to Earth, not just producing but doing all the vocals and instruments himself. Reviews, reasonably, cited Van Morrison, Cat Stevens, Neil Young, and acoustic Led Zep as influences, in keeping with references often made with his early work. But the material showed the emotional maturity of a man approaching 50 (he’s 51 now) with kids leaving and new phases of life on the horizon.

Long Way Home, the first album on his own new Liula Records label after spending his career with RCA, expands on that, the semi-nomadic situation becoming part of the creative process. “I didn’t have my full studio set-up,” he says. “I had my board, which I carry with me, a full 16-channel analog board, taking up all the living room. So I recorded as much stuff as I could, just did them myself. And then there were other songs where I needed help. That’s when I roped Seth in. He’s been a good friend since the Supernova sessions [on which he played], and we hit it off at that time.”

More recording was done at Kauffman’s place, and some more at drummer Ariel Bernstein’s. It came naturally, from that soulful opener to his trip into the mystic of “Yearning” to the Neil Young-evoking ode to an illusive wanderer, “They Call Her California.”

And a couple of surprising highlights are interludes with no words, or at least no concrete lyrics. “La De Dum, La De Da” is a lilting ditty, featuring only those titular syllables in gorgeously layered vocals. And with “So, Damned, Blue” he takes a breath toward the album’s end, its spare acoustic chords perhaps reminiscent of the atmosphere Fleetwood Mac founder Peter Green created on his dreamy “Albatross” in the late 1960s.

“I felt really good about it,” he says. “I knew the songs were happening. I knew they were coming to me, so I was just trying to capture them, just like always. It’s like trying to catch fireflies.” And that is the perfect image for the title song, which closes the album. Flowing right out of “So, Damned, Blue,” the song picks up the album’s thread with a nostalgic portrait of growing up in New Hampshire and Utah, wandering all day, interacting with the world right around him until his mom called him in for dinner.

“As I’ve gotten older, now that I’m 51, I can look back on this and see what a gift my childhood was, when it just revolved around your friends and your bikes and life was yours on the weekends and after school and summertime,” he says, lost in those mental pictures. “Oh, man. Summertime was wonderful. I felt lucky that that song came out the way it did.”

Well, there is a caveat in the song’s final couplet:

Winter comes to us all, my friend

Just as every childhood has an end

“Yes,” he sighs. “I suppose that’s the reality of our, you know, impermanence.” Says the man hunting for a centuries-old house.

To see our running list of the top 100 greatest rock stars of all time, click here.

Source link